A Passion for Clarity

The J. Krishnamurti – David Bohm Dialogues in Perspective

By Bill Angelos

Do not be afraid of that word `passion’.

Most religious books, most gurus, swamis, leaders,

and all the rest of them, say “Don’t have passion”.

But if you have no passion, how can you be sensitive to

the ugly, to the beautiful, to the whispering leaves, to the sunset,

to a smile, to a cry? How can you be sensitive without a sense of passion

in which there is abandonment? Sirs, please listen to me, and do not

ask how to acquire passion. I know you are all passionate enough in getting a

good job, or hating some poor chap, or being jealous of someone; but

I am talking of something entirely different: a passion that loves.

Love is a state in which there is no `me; love is a state in which

there is no condemnation, no saying that sex is right or wrong, that

this is good and something else is bad. Love is none of these

contradictory things. Contradiction does not exist in love. And how

can one love if one is not passionate? Without passion, how can one

be sensitive? To be sensitive is to feel your neighbor sitting next

to you; it is to see the ugliness of the town with its squalor, its

filth, its poverty, and to see the beauty of the river, the sea, the

sky. If you are not passionate, how can you be sensitive to all

that? How can you feel a smile, a tear? Love, I assure you, is

passion.

J.Krishnamurti

The Premise

During his lifetime and since, J. Krishnamurti has been acknowledged as one of the great spiritual teachers of our time. Paradoxically, it is also widely known that one of his final statements just moments before his passing was that despite his more than 60 years of travelling around the world and speaking to more people than any other spiritual figure in history, no one had succeeded in achieving the quality of consciousness in which he had lived most of his life. Perhaps this is true. Nevertheless, a quarter of a century after his passing, there exist countless indicators pointing to the very real possibility that of the hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of people whom he touched in his lifetime – and continues to touch through books and tapes of his talks and dialogues, a significant number of them have undergone some form of transformation as a result of that contact; and a consequent understanding – at least to some degree – of what this most unusual human being was trying to communicate.

Some may argue that this can also be said of other influential figures, from Jesus to Hitler to Mao. It is only when one examines that word “transformation” closely that they can perhaps discern why the transformation that Krishnamurti speaks of stands apart from all the others. According to him, the difference lies in the source of the transformation – specifically, whether that source is within the realm of thought or beyond it; the latter requiring not only a verbal explication but a non-verbal perception and insight. What that source may be can only be answered by observing one’s relationship to life. It alone will reveal whether that transformation is a dynamic living thing, free of assumptions, with no fixed purpose or goal – or merely a change in belief or point of view.

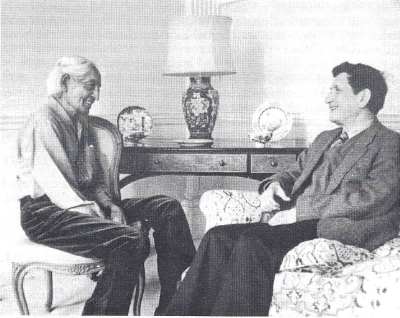

Of the many who watched their lives change direction and meaning as a result of their contact with Krishnamurti, one man stands above the rest, if only because of the manner in which he communicated what was taking place in his life to the rest of the world – Theoretical Physicist David Bohm. As a scientist, it was imperative for Professor Bohm to understand how, whatever he encountered in the world, also fit into what was known about the laws of nature and their concomitant manifestations in the physical world. Such was the case when he learned that Krishnamurti’s perception of what was also a fundamental underpinning of Quantum Physics – the relationship of “the observer and the observed” – were one and the same. As a complement to this fact, few realize the degree to which the meeting of these two minds – which occurred as a result of their individual understandings of “the observer and the observed” – would help shape Bohm’s revolutionary “Implicate Order” concept. For from the day they met in 1959, to 1992 when he put the finishing touches on his epic re-examination of the material world entitled “The Undivided Universe”, Dr. Bohm never stopped finding new ways to creatively communicate the importance of the relationship of “the observer and the observed” — even beyond the realms of physics. Similarly, Krishnamurti also knew the day they met, that perhaps he had found someone who could help him communicate what it was about the way he perceived the world that was decidedly different from the way the rest of us saw it.

So it was, that this new approach to Perception became the underlying focus of the more than 30 dialogues these men engaged in over a period of almost 30 years in an unprecedented investigation into what defines us as a species and what our potential as human beings may be. Moreover, it became increasingly clear to them, that if this unique quality of perception Krishnamurti was evidently born with was an actuality , it was vitally important that all aspects of it could also be explained in as scientifically precise language as was possible . For there was reason to believe that the future of humanity might just hang on its comprehension by others, as well. And yet, in those same Dialogues, both men also made this very clear: Though neither was naïve enough to think that what they had to say would be understood by enough people in time to avoid what seems to be a relentless path towards the total annihilation of our species and the planet we inhabit, they never stopped communicating it. Why? Because it was the right thing to do. What follows is presented in the same spirit. – It’s the right thing to do.

Origins

The JK/DB Dialogues can be roughly divided into the four decades during which they occurred. Although the content of each of them is unique in its own way, when examined in their totality, there exists a certain inherent continuity that has, up till now, been overlooked.

The first series took place in the 60’s, the second in the 70’s, and the third in the 80’s. I have added a fourth series during which the spirit of the first three was always present. It took place between the years of JK’s passing in 1986 and DB’s passing in 1992. Few are aware of the fact that Bohm would carry on the investigation begun by both gentlemen In a series of seminars he held during that period on the nature of Consciousness. For seven consecutive years, he continued to conjure up new, creatively original, scientifically-based approaches to articulating what he had explored in so many different ways with his friend Krishnamurti in prior years. In doing so, Professor Bohm left a legacy that might be explored by others via various scientific disciplines. That is precisely what happened – quite unexpectedly – in the author’s case.

The seed for this project was planted about five years ago while writing about an experience I had working with a former classmate who had become a world-renowned brain scientist – Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita, MD. Half a century after we had graduated from the equally renowned Bronx High School of Science – which lists eight Nobel laureates among its alumni – I received a phone call from Paul who had learned that I was now living in the state of Wisconsin, not far from where we he was now a tenured professor in Rehabilitative Medicine and Biomedical Engineering at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

He was calling to invite me to come and see the latest iteration of an amazing invention that I had first read about 30 years before in NATURE Magazine. The article told of how Paul had built a device that made it possible for blind people to see, tactilely – that is through their skin surfaces. I accepted his invitation and during my first visit I also learned that this same device was now also being tested by Bach-y-Rita and his colleagues as a means of restoring balance to equilibrium-challenged people. Nevertheless – after 3 decades! – the obvious merits of Paul’s invention remained unappreciated if not totally ignored. Moreover, he was in need of $50,000 so that he could move his facilities off campus and start a commercial venture; reason being the University held the patents on Paul’s inventions and he was prohibited in doing so, while his laboratory and office were still on campus.

Although the required funds were beyond my means, I offered to help in my own way. I built a website for Paul that I called “My Friend The Miracle Worker”, upon which I began posting daily videos I was shooting of his device in action, as well as commentary about Paul’s work. Within six weeks, the website attracted the attention of an investor who provided the needed money. Soon after, Paul moved his offices and laboratory off-campus, I moved to Madison and our work relationship officially began.

On the very first day, as I was videotaping Paul explaining to me where he was at that point in his research, he mentioned that his device had its origins in the work of a psychologist named James J. Gibson. But I paid little mind to the name, since so much else was being absorbed. It would be quite some time before I recalled that David Bohm’s work had also been greatly influenced by Gibson. And it was only then that I would also learn that Gibson had in fact revolutionized our scientific understanding of Perception, which led to the establishment of a new discipline he called “Ecological Psychology”.

But even before then, what had linked Paul’s and Dave’s work in my mind was when I learned that Paul and I had encountered a very unusual word in our past experiences – Proprioception.

I can’t remember who mentioned the word first, but I would soon learn that Paul had used it in a paper he had written while he was still in Medical School in Mexico, back in 1960. Although the paper was written in Spanish, its content was so insightful and unusual, beginning with the inclusion of that word in its title, that it attracted the attention of the head of the Brain Research Department at Harvard University – Dr. John F. Fulton. Fulton called Paul and asked if he would send him a translated copy of his paper. Evidently Fulton’s now deceased colleague, Nobel Laureate Sir Charles Sherrington, had initially identified and actually coined the term “proprioception” half a century before, and he’d done so while studying the very activity that Paul’s paper was about – proprioception’s relation to extra-ocular muscle activity and eye movement.

While I was intrigued by Paul’s understanding of proprioception in the classically accepted physical sense, what heightened both our interests, was when I told him that years before, I had been introduced to the word in an entirely different context.

Proprioception was the cornerstone of a series of annual Seminars David Bohm held between 1986 and 1992 on the nature of Consciousness. It was during these Seminars that Bohm first suggested that perhaps it was possible to develop a kind of awareness of certain aspects of Consciousness – specifically our thought processes – that parallels our innate awareness of our physical bodies in space, which is made possible by what is known as proprioception.

Why would anyone want to develop such a capacity? One of the recurring themes of the Krishnamurti/Bohm Dialogues was an inquiry into the nature and limitations of the thinking process and the inherent flaws in a system that uses itself to solve problems caused by its own limitations. Primary among the problem-causing limitations was an element called “fragmentation”, which Krishnamurti had spoken of since the early ‘30’s and Bohm had dealt with extensively in his classic book, published in 1980, “Wholeness and the Implicate Order”.

The Dialogues – which were, in actuality, co-investigations – would lead to the possibility of bringing into play a form of non-verbal insight that might be able to perceive the dangers of self-deception caused by fragmentation and avoid them, much like one sees the edge of a cliff and knows not to go beyond it.

Bohm re-introduced this aspect of his Dialogues with Krishnamurti during his Consciousness Seminars. But he did so, using scientifically valid terminology. He found the term and its proper application in the works James J. Gibson who worked in tandem with his psychologist wife, Eleanor. Mrs. Gibson’s own distinguished research in the field of perceptual learning as it pertains to early child development, has been acknowledged for its groundbreaking insights. Principal among these, were her studies with infants which showed that the above-mentioned awareness of the dangers of surface edges, was indeed learned at quite an early stage.

From the time we are born, we begin developing an awareness of how to move our bodies. Watch a newborn as it attempts to control its movements and compare it to its capabilities to do so at 6 months and then when it begins to crawl and then walk. That is all learned behavior.

But what is learned is not accumulated in the form of “data”. This kind of perceptual learning is of an entirely different nature. Once the process – for example, crawling – is understood, it is no longer re-called from memory, but becomes an innate aspect of the subject’s ability to function in its environment.

James Gibson had simultaneously discovered that proprioception was the direct link between body and mind that made perceptual learning possible . In fact, said Gibson, our “senses” are by no means passive stimulus-response mechanisms, but active perceptual systems that are, in effect, modes of attention. It was an entirely new way of understanding the true nature of proprioception and its relationship to actual movement . (NOTE: Many athletes approach this proprioceptive form of learning in an open-ended fashion – often with spectacular results).

Bohm was well aware of the work of Gibson and his team of researchers. He further surmised that since he and Krishnamurti had identified thinking as a material process whose primary characteristic is also movement, perhaps what they were talking about during their Dialogues, was the possibility of developing a similar purely proprioceptive approach to watching thought. If this was possible, a similar kind of perceptual learning about the process of thought might also take place – with similarly open-ended results. It was during his Consciousness Seminars that he first introduced this notion in the form of a proposal which he called “Proprioception of Thought”.

All of this was recalled when Dr. Bach-y-Rita and I first realized that each of us had encountered “proprioception” years before, but in entirely different ways.

It took a while to percolate in my mind, until one day I had an epiphany. Up till then, neither Paul nor his colleagues could explain the amazing residual or “ therapeutic” effect of his invention, which they had accidentally stumbled upon . When used in its balance-enhancing mode, subjects were able to maintain that balance even after they had disengaged from the device. Yet, there seemed to be no scientifically valid explanation for this phenomenon. If, however, this co-mingling of the psychological and physical aspects of proprioception was true, then some form of perceptual learning was taking place that enabled the subject to maintain their balance even after disengaging from the device for at least a short period of time. I mentioned this possibility to my friend Paul, and we were suddenly off on a mutual quest in a new direction — to discover the “core mechanism” of his invention which made perceptual learning possible.

We soon also observed that as the subjects continued to use the device, this learning in the form of a residual or therapeutic effect was lasting for increasingly longer periods of time, much like the crawler eventually becomes a stable walker and then even a runner. After a few months of observing (and videotaping ) subjects, before, during and after their sessions with the device, I began writing a book about our observations. Prompted by psychologist James J. Gibson’s radical re-interpretation of Proprioception, which rejected Physiology’s generally accepted view of it as a purely physically-based phenomenon, I titled the book “The Proprioceptive Self” .

When I showed the title and the first few pages to Paul, he responded more than approvingly — he graciously asked if he could write the book with me; certainly validating the notion that this was a track worth pursuing. Here’s the opening sentence of that first Chapter to which Paul responded so enthusiastically:

The Proprioceptive Self

Proprioception provides us with a physical and psychological foundation upon which we can extract self-meaning from all sensory input.

Sadly, life got in the way of Paul and me continuing on that track of exploration as a team. Soon after we’d started our joint inquiry, Paul learned that he had contracted lung cancer. My brilliant friend of more than 50 fifty years has since passed away.

It was only after both he and David Bohm were gone and I began giving serious consideration to developing a project about all this, that I learned that Bach-y-Rita and Bohm had something else in common, besides their mutual interest in the word proprioception.

Fortunately I had videotapes and audiotapes of my many conversations with both men and as I began reviewing them all, things started falling into place: Back in the early ‘60’s although each man’s scientific discipline was light years away from the other’s, their respective research paths were inspired and informed by the work of the same person, James J. Gibson and his revolutionary insights into Perception. On our first day of videotaping in January of 2003, Bach-y-Rita, clearly stated how Gibson’s landmark book “The Senses Considered As Perceptual Systems” was the direct inspiration for his invention. As for Bohm, while reviewing one of our extended recorded conversations, I was reminded of what he said about how the trajectory of his work had been dramatically altered when, in their dialogues in the early ‘60’s , Krishnamurti had introduced the notion that “perception through the mind was primary.” Bohm marked the importance of that development in an extraordinary appendix that appeared in his book “The Special Theory of Relativity”, which he titled “Physics and Perception”. It was in that appendix that he mentions Gibson as being one of the psychologists whose work was a formative scientific influence. He also mentions the importance of perception in his work in this clip from a videotaped conversation we had in 1990:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mst3fOl5vH0

By then, I too was inspired enough to spend the next few years exploring Gibson’s work. During this period I also contacted the Bohm Archives at Birkbeck College in London, England to inquire into the possibility of gaining access to the recordings of all the Bohm Consciousness Seminars – my initial intention being that they might form the basis for a series of seminars that would revisit their content with “different eyes”. The more I looked into that content, the more I realized its undeniable relationship to the content of the Krishnamurti/Bohm Dialogues. I would soon also make contact with the Krishnamurti Archives in the Brockwood Park School, which is also in England.

And this project was born.

Nexus

No two people were less inclined to meet during their lifetimes than J. Krishnamurti and Professor David Bohm. Were an imaginative novelist to conjure up the circumstances behind their actual meeting, a prudent editor would more than likely suggest that the writer at least give his creation some additional thought. Nevertheless, what follows is a verbatim account of how that meeting of two of the most unique minds of the 20th (or any other) Century did, in fact, come about – from two of the individuals who were there when it happened, David Bohm and his wife Saral.

In 1990, I was invited by Professor and Mrs. Bohm to join them in Holland because, at the time, he and I were deeply immersed in writing his biography. He’d been invited to Amsterdam to participate in a Seminar entitled “Art, Science and Spirituality in a Changing Economy”; a week-long event that had quite an impressive roster populating its planned five or six daises. Professor Bohm’s dais included his good friend, The Dalai Lama, renowned abstract artist Robert Rauschenberg , and a Russian Economist, who was an inside member of the then in power Mikhail Gorbachev regime.

The Scene: The atrium of the 5-star “Golden Tulip Hotel” in Amsterdam Holland.

It was late in the afternoon – teatime to be exact. We had just returned from one of the daily Seminar sessions and we were now meeting to go over how we might approach a request from Holland’s national television service TELEAC, to do a one-hour interview with Professor Bohm on the following day. He had agreed to do it if they would allow me to be the Interviewer.

We decided that I would attempt to trace Professor Bohm’s interest in Consciousness and how it related to the development of his work in Physics. We’d do it by chronologically going through his many published books, while simultaneously tracing his changing awareness of the nature of Consciousness – the first incident having occurred when he was a little boy. In a prior conversation, Professor Bohm had already revealed to me that he was once asked by the famous Science historian Carl Von Weizsacker how it was that a theoretical physicist of such eminence should delve into the nature of Consciousness. Bohm’s answer: “To me, it’s all one movement.”

As I made notes about how we might talk about that “movement”, Professor Bohm said he would be alluding to how its direction was dramatically impacted by meeting Krishnamurti. That’s when Mrs. Bohm (Saral) interrupted and said: “Did I tell you about the very first meeting?”

I said, “No…”, reflexively raising the pick-up level on my mini-tape recorder sitting on the table in front of us.

Saral said, “You should really get it down, actually.”

And, as we were served tea while the piano — in bizarre synchronicity — played “Getting to Know You” and “Over the Rainbow” in the background, this is what was recorded.

NOTE: You’ll have to listen closely, but it’s worth the nine minutes of attention that is required.